In this episode, we have two segments.

Ben Passmore

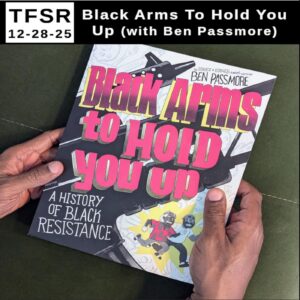

First up, Ian talks with Philadelphia-based cartoonist Ben Passmore about his new book, Black Arms to Hold You Up: A History of Black Resistance. They discuss the research and making of the book, Passmores anarchism, the themes of inter-generational struggle, contextualizing history through lived experience, and the pitfalls of mythmaking. In addition, they spend some time discussing Ben’s martial arts practice and the legacy of Assata Shakur in light of her recent passing.

Other titles by Ben:

- Your Black Friend and Other Strangers

- BTTM FDRS

- Gumroad store

- LinkTree

- Patreon: @DayGloAHole

- Instascam @DayGloAHole

- BluesKry: @BenPassmore

- Fedbook @DayGloAHole

- Fumblr @DayGloAHole

Mikolo Dziadok

Then we’ll hear a brief interview with Mikola Dziadok, a Belarusian journalist, anarchist activist, blogger, and former political prisoner. Mikola is now about 3 months out of prison and starting a new life in exile. The interview was conducted in mid-November by comrades from Frequenz-A and appears in the December 2025 episode of B(A)D News from the A-Radio Network. Check our show notes for links on how to support Mikola’s next stage of life

Follow Mikola’s Channel in YouTube: www.youtube.com/@Radixbel

Support Mikola financially (it is needed for setting up life in a new country):

- ko-fi.com/mikoladziadok

- mikola.dziadok@gmail.com – PayPal

- 1K17NNNwFvH3rfg44vkLW1zHJCvxG8 Sc7z – Bitcoin

. … . ..

Featured Track:

- Keep On Keeping On by The Impressions from Dead Presidents OST

. … . ..

Transcription

TFSR: Okay, we’re here today talking with Ben Passmore about his new book Black Arms to Hold You Up, out from Pantheon Press.

Ben, can you introduce yourself to listeners? And maybe talk about your pronouns and any affiliations you think may be relevant to our conversation?

Ben Passmore: Oh, sure, yeah. I’m Ben Passmore. He/him. No formal institutional affiliations… you know, being an anarchist or whatever. I am loosely affiliated with Kupigana Ngumi, which is a Pan-African martial arts and study event. And the neighborhood martial arts project. I go in and out of being the striking coach over there.

TFSR: Okay, thank you very much for that. My first interest is in comics. I wonder if you could maybe talk a little bit about how you found your way to illustration and comics and cartooning?

Ben Passmore: Oh, yeah. I think for people around my age, nerds around my age—which is 42—I got into comics as a kid during comics’ grim, dark era. Lots of spikes, lots of leather vests. The first comic for adults that I got into was, was Spawn that my babysitter passed to me as one blerd, recognizing an emerging blerd. He gave me a bunch of a bunch of video games and some Spawn comics. That sort of kicked off my love for it. I read Peanuts and Garfield and Calvin and Hobbes when I was a kid, but Spawn really made me want to draw. I used to just spend a lot of time in my room trying to redraw panels from the Spawn comic—all those little chains and spikes and stuff. That’s kind of where it started for me.

TFSR: And did that precede finding your way to politics?

Ben Passmore: Yeah, most definitely. I was slightly precocious, politically, as a kid, but I was mostly just like a little criminal, which, depending on who you ask, wasn’t being… it’s not being particularly very political. I didn’t get super locked into any kind of politics at all until I was a teenager. I got sent to a troubled teen school, which people are pretty familiar with now. I caught a felony for possession of stolen property, and I ended up in the school for more or less four and a half years. In the library, they had—pretty randomly—this book called Look Out, Whitey! Because Black Power’s Coming to Get Your Mama! by Julius Lester. That is a book that is about—no one being surprised to hear—the history of Black power. That sort of kicked it off for me. I got into Marcus Garvey shortly after that. I read some of a Cornell West book, all while I was at the school. That gave me a bit more context for American history

TFSR: As an aside, have you written/cartooned about that experience?

Ben Passmore: In this book, I refer to it a bit, trying to contextualize the reason why I was tackling this particular history, the black radical tradition or black liberation in general. But no. I’ve never written really at all about my time in reform school, although I’ve been thinking about it.

TFSR: I enjoyed this book very much. It was my first exposure to your work. I subsequently went back and got into the other stuff, and I enjoyed that as well. Can you talk about the genesis of this book? How long was it in the making and how it changed over the course of its production?

Ben Passmore: Yeah, thanks for that question. Well, there’s a couple different answers to it. Some are sort of like a little more inspiring than the others. I usually like to just mention them both. Let’s see, I had been sort of going back to the Black radical tradition, maybe about seven years ago or more. I had been radicalized by it as a kid, and then when I got out of reform school, I went to college. I got connected with anarchists and got put on to anarchism. A lot of my first praxis stuff— things I was actually doing outside of just reading things—was with anarchists. Within that milieu, there was a lot of skepticism of the Panthers and certain aspects of Black radical history. At least at the time, anarchists tend to be a lot more interested in the BLA if anything. I sort of pushed off the black radical tradition as an area of focus and inspiration for me.

Then maybe around Ferguson, in particular, I found myself feeling a little burnt out by a mostly white anarchist milieu. And feeling like I had run aground on a lot of different ways that I had been approaching things. I started just going back. That’s happened to me at different times in my life where I’ll just go back to the black radical tradition and start studying things. I found this book called Black Panther Reconsidered. It was an anthology by a bunch of rank-and-file Panthers. I don’t think there was any… you know, no one wrote in it that was part of the Central Committee or anything. They were really focused on talking about their experiences in the party as now grown-ups, because most of the Panthers were very young, and talking about sort of misconceptions that surrounded the Party itself. I appreciated the reflection. It was very different from the hyper romanticized view that I’ve been used to.

Over time, I was studying more and more. I was reading more and more. I got more connected in my personal life with a lot more nationalists, a lot more Pan-Africanists. They became part of my friend group. And I mentioned Kupigana Ngumi I do some projects now with people that are Pan-Africanist. That was happening in my life. My life was just changing with me trying to sort of address the contradictions between my anarchism and a kind of growing nationalism, or at least a sympathy for it. And then 2020 hit.

Around that time—and this is the non-romantic part of the story—my agent was asking me what I wanted to pitch. He was like, “this may be a good time for you to pitch a book and get out of your indie comics world stuff.” His initial suggestions were things I didn’t want to do. Sort of like how to be an activist, or something like that, which… I didn’t want to do anything like that. But I said, “Well, you know, the way that I’ve learned how to do a lot of what I do in my life is through studying these people and their contexts.” Both the things that are really exciting and the things that are not so exciting. Learning from people’s successes and failures. So I more or less suggested that we pitch a book that was covering about 100 years of history. More or less that’s how we got here. The book itself… I signed the contract in 2020, so on the books, it’s about five years, but I started researching before that. Overall, the book took about seven years and the drawing section probably took about a year and a half, two years.

TFSR: If I could maybe go back to the beginning of your answer here. Reading about rank-and-file Black Panthers. I’m trying to think of how to phrase this…you’re getting the story without all of the myth-making, is my impression. I wonder. It sounds like that was very valuable. But I wonder if you could maybe drill down a little bit further and maybe talk about what in particular the value of that was? If you indeed did find it valuable.

Ben Passmore: Yeah. Well, I think that there is this overall tendency within whatever you want to consider “the left.” There’s this tendency to be really wedded to romantic aspects of struggle. Even outside of the this Black liberation stuff, I remember being a younger anarchist and reading all these Crimethinc. books and thinking that like, “Oh, you know, this is all good. This is all positives. I’mma feel like anarchist Rambo.” And then a bunch of years later, being like, well, I actually have a whole lot of PTSD from running around in these streets, you know?

TFSR: Right.

Ben Passmore: I understand why maybe that isn’t addressed. But I think it made it difficult for me to understand that I was being traumatized by certain things, and also think about how to address it. There was a whole lot of shame that I carried for a while of feeling negatively impacted by things that make sense. You know, you get choked out by a cop, or you get attacked by a Klan member. These are traumatizing things. So I think, sort of similarly, Panthers that have tried to reflect in a very clear-eyed way about what was both good and not so good about the party and their personal experiences—and also what they think they would like to see approached differently in future generations, trying to sort of apply these ideas.

I think it just gives you tools. It gives you tools for how to recognize abuses of power. Assata Shakur wrote a whole lot about how patriarchy contributed to just a lack of cohesion in the party. Ashanti Austin also talks about that quite a bit. But also lesser-known figures, like Safiya Bukhari, who was in the BLA and in the Republic of New Africa, wrote quite a bit about her experiences in both the party and in the BLA and the long term effects and reflections of those things. I think one of the valuable experiences, or the valuable tools that I got from anarchists specifically was just a practical… This tendency to read theory and history in order to to apply it. You’re trying to come away with tools. It’s not so much—or at least in the milieus I was in, it was not so much about being like “rah rah” about the things you’re reading and sort of make role models out of the people we’re reading about. You know what I mean? Obviously, people like Ashanti also should be respected and appreciated. But even he himself would be like, “I’m not a hero, I’m a comrade. I’m out here. I’m still learning.”

I think for me with books like Black Panther Reconsidered it was very similar the way that most people wrote about it. They were like, “We should always understand as ourselves, as people who are changing, who are evolving. Rather than thinking of that time and ourselves as mythical figures.” There’s also the book Comrades, too, which is rank-and-file members who are also writing about it in that way. I think, in my experience—if I can be messy—I think honestly most Panthers I’ve interacted with interpersonally speak about the party in that way. Trying to talk about where they saw ways—outside of COINTELPRO—that the party itself, or members in it, contributed to the dissolution of the party. In my experience, it’s more central committee members or people who are maybe not even in the party for real who seem to be really obsessed with myth making.

TFSR: Yeah, yeah.

Ben Passmore: You know what I mean? Like, interpersonally or in conversation won’t cop to any sort of like shortcomings.

TFSR: Thank you for that. I read this book in conversation with a lot of the quote, unquote “graphic histories” of recent years. I feel sought to encapsulate histories of social movements into more digestible graphic narratives, probably for people who are wholly unfamiliar with them. I think that you maybe know the kind that I’m talking about, the kind that you would see in not necessarily a radical bookstore, but maybe a more mainstream bookstore, for instance. What do you think the pros and cons of those books are? And do you see Black Arms to Hold You Up as a repudiation of that format, or more of an addition to that canon?

Ben Passmore: Yeah. Well, I do think I know what you’re talking about. I mean, there’s an enormous—outside of political subjects, this is a huge market now for nonfiction histories. I think there was a time when there wasn’t a clear market. I think all of (us at least in the United States) who are producing nonfiction comics of of this type, are responding to… Maybe our two gods are Art Spiegelman and Joe Sacco, both who produced those books when there wasn’t—well, I mean, Art Spiegelman, we have the term graphic novel because of his publishing, you know?

TFSR: Right.

Ben Passmore: I think particularly from an anarchist perspective, story writing is an inherently flawed way to approach the way that we want to talk about social movements. Because the easiest thing in the world is to pick a singular person and sort of drape everything that happens around this person. And then before you know it, for lack of an easier sort of narrative of device, you’ve created some great man [14:48 *bleep* bullshit*.] So I think it’s always tricky, because you only have so much space and comic books can be a difficult way to capture a lot of detail. You know what I mean?

I wouldn’t say that I was repudiating anything in this book necessarily. I think that my entry into this history, was trying to personalize it and also tackle sort of the idea of thinking about who we get this history from. Like, I myself got it all out of order, often from books but also from elders—very imperfect people themselves with imperfect memories. I think a lot of engaging in Black history in general is understanding that this idea of a scientific truth can be problematic. You’ve got to locate your identity and also the energy to do something with it. To engage in struggle, even if you don’t know if everything you’re hearing is a fact, right? I wanted to talk about certain people and certain periods in history and kind of what happened. But I also wanted to sort of pull apart this idea that there can be a definitive survey of this history.

I don’t want to put any spoilers, but I tried to pull the rug out a bit from the reader at least once or twice in terms of those things. Because I feel like the books— these books are commodities, right? These are largely only possible because someone, somewhere, decided that it’s worth some money. There’s no particular investment in Black armed struggle, as far as I can tell specifically. It’s like they come about by accident. I feel very fortunate that I was able to make exactly the book I wanted to make. But my hope… and a large reason that I put a whole reading list broken down by chapter in the back of the book. I hope that people don’t take this book—as they do with other books of this type—to read the book and think, “Okay, well, I got it. I don’t need to engage in any other media around this. Maybe I’ll wait for the movie to come out.”

I wanted people to walk away with a lot of interest, but hopefully a lot of questions. And this desire to then go out and read more about certain people, certain ideas. I tried to have in the back of the book, just a wide swath of different kinds of material. Anyone who is really interested in Black liberation, in the Black radical tradition, you’re incredibly fortunate. Because the majority of the writings are incredibly readable. Even if you just wanted to read the major figures, if you wanted to read about the Republic of New Africa’s ideas, Imari Obadele wrote War in America, and it’s incredibly readable, even if you disagree with him.

TFSR: Along those lines, I did find the reading list at the back very illuminating. You mentioned some of the research that you did for the project. I wonder if maybe you could speak to it. Seems like you sought for a mix of archival sources and academic contextualization around the subject matter, but I felt like you gave greater weight to the words of the organizers themselves. I wonder, why is that so important?

Ben Passmore: Yeah. I think like a lot of people, I have—well, maybe not like a lot of people—I have both a deep respect for the discipline of study and of researching. I certainly learned a lot about it researching for this book. Although I had done quite a bit in my career, so to speak, as a comics journalist. I’ve done some short-form history pieces before this that required quite a bit of research. So I have a lot of respect for that, but also I have quite a bit of skepticism when it comes to academics themselves and certainly the institutions, right?

When I was approaching this book I wanted to be able to stand on things in the book that I was purporting as the truth, right? I wanted to have enough sources so that I felt confident that when I stated something or framed something in a way that was true that if someone challenged me, I’d be like, “Well, no. Here’s why I am almost certain that this is true.”

I think something that is difficult is that it’s just really hard to know who to trust. I think going back to the Panthers, or maybe more specifically, thinking about Assata, right? We have Assata’s account of her life, including the attacks that she was charged for. She says that she is innocent of all the things she was charged for. We have some sort of indications from other BLA guerrillas—not all of whom would have been in the same cell as her, but who say more or less that she was not a shooter. Although she was really essential. But you know, they’re never going to tell us exactly what what she did or not. And, of course, they shouldn’t. But the most detailed story we have about “what she did” is from the FBI.

Assata says herself that basically the FBI accused her of anything in which a Black woman was a participant. So we have this sort of like weird game of telephone where I think some of us really like the idea of Assata as the bank robber, as, you know, someone who shot police. Or at the very least, we have no problem right with that depiction of her. So it can be sort of hard. We end up walking away with this sort of mixture of propaganda from the state and insinuations from her book and other BLA people. It’s gonna be really hard to look at what the truth is.

I think at the end of the day, who I was trying to platform were the people who put their lives on the line for our liberation. In many points, my character literally responds with maybe not another perspective, but a degree of skepticism or maybe an attempt to contextualize what they’re saying. But overall, I felt like it was just important. More and more these people are sidelined or disappeared or not listened to. So it felt important for them to be platformed in that way, even though it’s ultimately imperfect. I guess what I’m saying is I don’t know that there is ever a way to write about any anti-colonial struggle that didn’t win in a way that’s like, “100% this is the way that it was.” It’s even tricky to do that, because the state uses the contradictions, the complexities, and the shortcomings of any movement against it, right? It uses it to delegitimize it. It can be just very tricky to try and talk about the truth.

TFSR: My reading of this is that it is essentially anarchist in its depictions and critiques of organizations, however influential they may have been. Would you agree with that? And what do you hope readers will take away from your depictions of these movements, especially as it relates to power? Or, leadership rather?

Ben Passmore: I think one struggle for me in in making this book is that I didn’t want to have my anarchist analysis just like saturated in the book. I wanted to base my institutional critiques. or my critiques of patriarchy and things like that be based on sources that I was reading. Once again, talking about Assata, she critiques very much a lot of the patriarchy and the gender dynamics within the party. Ashanti Alston has done a lot of extensive writings also. Ashanti is an anarchist, but you know, Assata is not—very much not.

So most of the critiques are based in something other than just my general… you know, me putting my anarchist nose up at institutions and hierarchies. I think overall what I wanted was to make a case for what I think was really beneficial about this history. I wanted to respect people’s effort. I think some of the things that are very strong about the Black radical tradition is that it’s based in lineage and history and cultural struggle. Often—and I want to be careful when I say this—but I think often there’s this insistence on emphasizing a certain group’s political tendency as it relates to a European political tradition in this way that I think misunderstands the pragmatism of the black community as it pertains to politics. I think there’s a lot of people that sort of talk about themselves, like…, Well, here’s an example, Robert F. Williams. He wrote Negroes With Guns, a book that was studied by the Black Panthers. Famous for running the Klan out of Monroe after a gunfight. He talks a lot about this relationship he had with Trotskyists. He interacted with a lot of different kinds of communists. And both respected how they moved and also saw a lot of similarities between these concepts within communism and the Black church in the South. He felt like he didn’t need to engage with communism because there was enough similarities. He was like, “I’m already a Black southern Christian”, you know? And I don’t know about that [laughs]. I don’t know that I agree with him, but that’s how he felt.

I think that speaks to a bit of the pragmatism of this movement where people are really… They’re trying to get free. They’re trying to get free together. There will be certain ideas that people take hold of because it seems like it will work, but it’s very rarely people’s whole identity. Even the Panthers, people would be like, “Oh, they’re a Marxist-Leninist organization.” They contained what people would consider liberals now. There was tons of anarchists in the Panthers. There was a bunch of, a huge amount of Nation of Islam people. It’s like they kind of took everybody. So I think being overly fixated on the tendencies of this group, I think is sort of making a mistake. And kind of seeing what you want to see a little bit.

I think overall, the answer to what you asked what do I want people to get out of this? I think I don’t want people to feel discouraged. I think sometimes my work has… you know, I’m making jokes at the expense of almost everything. I think it can come off as nihilistic, but I think a lot of this is just sort of, like… people should read some of the jokes I’m making here, just as like playing the dozens with history a bit. It’s with love. I think, if anything, we should look at things and the shortcomings, and be like, “Alright, let’s pivot. Let’s try something different. They did this. It didn’t really work out this way.” Let’s keep it pushing with optimism, you know?

TFSR: What I took from this is sort of positing an inevitable perversion of goals and ideals. Or maybe not perversion, but maybe dilution of goals and ideals as these organizations rose to whatever level of prominence and power they managed to reach. I wonder if you would agree with that? And I wonder, if you do, what factors you think contribute to that?

Ben Passmore: I think the way that I structured things was more about… The book starts with Robert Charles, who’s all alone fighting 10,000 cop soldiers and racist farmers. It ends with Mikey Xavier Johnson, who’s fighting all alone against a bunch of Dallas PD, and is eventually blown up. I think what I wanted to… My focus certainly was not perversion. I think…

TFSR: I think that I used the wrong word there.

Ben Passmore: Yeah, no, I think—

TFSR: I think the second word that I used with dilution, but—

Ben Passmore: Right.

TFSR: Yeah, might be a little bit more apt to what I was trying… But go on, please.

Ben Passmore: I think the tough thing is that I didn’t spend a lot of time on COINTELPRO. In some ways, I think people will… The reason for that is that COINTELPRO—and just repression in general—can often be used by people that don’t want to reflect on deeper contradictions, deeper problems, they’ll just be like, “Well, this was the state. They sent some letters and had some people killed, and that’s why it didn’t work out.” It didn’t work out for a bunch of reasons.

TFSR: Sure.

Ben Passmore: But I think that that’s just common. I think you have an idea… like, I was talking to a friend the other day about something that seems like a bit of a generational divide between myself who’s a very old anarchist at this point, and some younger people. Sometimes people will come into a project that’s already formed, and they have their own ideas, you know what I mean? They get frustrated that their ideas are not being executed by the people who are already doing something. That’s just really not how it works, right? It’s like, your aspirations are one thing, but it’s gonna look different when you try to execute. That’s true for organizing. That’s true for comic books.

I think a lot of the people that are featured in this book have really big ideas. They’re really passionate, and they’re fighting against enormous odds. We’re talking about a subsection of 13% of the population trying to fight the greatest power on the planet. So, of course, the things they want to do are not going to work out. If they work out at all, it’s not going to work out really the way that they want them to. They’re gonna stumble. I think, if anything, I just want people to understand that as a matter of course. Then it doesn’t have to be altogether demoralizing. Failure is often like—it’s human, it’s funny.

There’s several people in this book that had—Safiya Bukhari—many different stages in her life. She started as a young college kid in the Panthers, and then as an older person, she got out of prison and she starts the Jericho Movement. She just kept it pushing. I think the major theme that I wanted to push was one that was about sort of ancestral connection. Was about the connective tissue between this hundred years of struggle. It’s all, in my view—and maybe this is controversial—but I just think they’re a part of each other. I think we should think of them that way.

And then, like, Ta-Nehisi Coates, who I don’t agree with on a lot of political stuff, but he gave an interview to Ezra Klein recently. In that, he talked about something that I really resonate with. It’s like we’re part of a tradition that fights knowing that we won’t see what we’re fighting for. I think that’s just the nature of of insurrectionaries. That’s the nature of rebels. Like we’re not fighting with this intense anticipation that we’re going to win. In the Black radical history, the Black liberation movement, that is just true. That is just true. Every generation has fought as hard as they could, more or less understanding that they’re not going to see the end. Whether or not that seems pessimistic or not, I think that is just a true thing.

TFSR: Given the intergenerational themes of the book, what are the qualities of your generation—I’m your age, so our generation, I guess—that you hope the next generation will keep? And what do you hope they they divest themselves of? What’s what’s working and what’s not working?

Ben Passmore: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. I think something that I struggle with is understanding the lack of interest in social projects. Like, a core part of how I got radicalized by anarchism was that I engaged with info-shops, projects like a really, really free market. I was part of the beginning of Food Not Bombs in Bushwick in New York. More than reading anything, it was engaging in these projects how I learned about anarchism. About what it means to move with people.

I guess I see with younger people, just this over reliance on being on social media, posting through it, getting really tied up in arguing about ideas… In this way that at least for me, was never overly important.

I spent most of my early anarchism in New Orleans, in a milieu that had a mix…we had some nihilists in there. We had some insurrectos. There’s even a couple weirdo radical, like self-described radical communists in there. We would talk about our fantasies. There would maybe be some tension around how we made decisions, or whatever. But all of that was part of just figuring things out. I worry that there is an increasing number of people who don’t realize that you really just got to get offline.

TFSR: Sure.

Ben Passmore: I say that knowing that makes me sound like the oldest man in the world. You asked about failures. I think—and I don’t know how relevant this actually is to the newest generation. Just thinking about this huge upswell of fascism and how the sort of generation that was out in the street fighting the Proud Boys is, I think, around my age and very much burnt out. I know, locally, a lot of people went through court cases and life stuff. So there’s not the same sort of presence on the street as there used to be. I think that presence is really, really important. I’m sad to see people burned out and not able to do that anymore.

That being said, I think, for me, something I had to learn was to balance out my skills. It was not enough for me to just be like a manarchist, dressed like a ninja, running around. Like, that was an inefficient way to move and made me a bit of a liability when it came to other… like, you know… [laughs] being able to emotionally care for people. Being able to understand all the things that people need.

I think that we can get in these habits of over-specializing and attaching our identities so strongly to a particular activity. I do see a lot more conversations about trauma. I see a lot more focus on mental health stuff. I think that’s really, really good. Certainly, when I was younger no one ever talked about those things. I would love to just see the synthesis of both. A lot of just being out there IRL, but also not just being “rah rah” all the time.

TFSR: To bring it back to the book, I think that your narrative works so well because, as you mentioned, you convey a personal stake in it. You bring yourself into it. And I wonder if you felt some resolution in the way it turned out?

Ben Passmore: Yeah, I don’t know. I think one of the hard things about making a book is that when you look at it when it’s done, when it’s published… You see the book that’s been made, and also every other possible version you thought of. It’s that scene in Avatar when he looks behind him and he sees all the previous avatars, you know?

TFSR: Right.

Ben Passmore: In some ways, it feels like you have to learn to love—you know what I mean? You learn to love the child you have, maybe not the child you wanted. I will say I was—more than any other work I’ve done—deeply personally changed by this book. I’m a wholly different person than I was when I started. I feel incredibly grateful for that experience. I feel incredibly grateful for all the people that trusted me with information, that supported me through this. I don’t know if it’s resolution. I think I’m in a place where I feel much more connected to people who are also engaging in this tradition. When thinking about the growing consolidation of power of fascists and what that means for, among other people, Black people in this country, it makes me feel more prepared for the fight that we’re in and the fight that’s coming.

TFSR: Shifting gears again here, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about training in martial arts and the whens and hows of that? And in what ways that has informed your work, if any?

Ben Passmore: So I got into Muay Thai. Now I’ve had a couple amateur fights in Muay Thai, which I didn’t expect to do. I got into it kind of in the way that a lot of people in my milieu did. My sort of idea of the insurrectionary anarchist is one in which you build skills. And one of those skills is training. A lot of the people that I met who are also in to Muay Thai or BJJ, when I was younger, they were also a similar kind of anarchist. I’ve been fight training for a long time, and I think it’s also not an accident that the Panthers, but also RAM and a lot of other Black revolutionary groups also practiced training martial arts and used martial arts training as one of the many ways they did outreach. So it is a bit traditional in that way.

I think for a long time, I just thought of it as a way that I can be in touch with my body, be physically fit, and also just be confident. If something happens… to not freeze up. Or have no idea about how I’ll respond if someone tries to punch me in the face. So it’s been good for that. I think more lately, I’ve come to understand the benefit of having martial arts-focused projects, having martial arts be a thing that you share with people. It’s a physical discipline. I think people maybe butt against the sporty nature of it sometimes.

I think something that was always a bit of a difficulty with a lot of anarchists that I would meet outside of my friend group was that there was this real resistance to… You know, it almost felt a bit like high school. People that they would think were jocks or something. Here, in the city that I live in, martial arts has done a really good job building this bridge between different insurrectionary or, like, anti colonial communities. I think that’s something that’s just really important.

A lot of different people came to anarchism after 2020 that weren’t into it before. There’s much more Black anarchists than there used to be. A lot of these people are coming from more authoritarian tendencies. I’ll meet people who used to be in the Nation. I just think that martial arts, from what I’ve seen, really created this nice sort of non-subcultural environment where people can trade skills. They can build trust. They can sort of get invested in each other’s health, in this way that I find very unique. It’s really become an enormous passion for me.

TFSR: Can you talk a little bit more about what you mean and what you’ve observed about people moving towards anarchism since 2020?

Ben Passmore: I think it was a couple things. But I think that the failure of BLM and similar groups led a lot of people to question hierarchical organizations, like protest organizations, organizations that are fixated on being part of government, or being part of the nonprofit-industrial complex. A lot of these people are maybe demographically very different from people who got into anarchism when I was younger. The anarchism that I got into was like very, very punk. Pretty working class. There’s a huge squat scene in New Orleans that I was a part of. I think a lot of people that we’re getting now, who are maybe not white kids that want to ride freight trains or listen to beatdown music. There may be more academics or something. But yeah, I think there’s a growing interest in anarchism.

TFSR: Yeah.

Ben Passmore: I think we can also see, not unproblematically, but this increased interest in identifying as an abolitionist. I think are people sort of, like flirting with anarchist concepts without having to fully commit. That’s something that I guess I noticed significantly after 2020, but I think there was a bit of a migration before that.

TFSR: Okay. Thank you for that. For my last question—in light of Assata Shakur’s recent passing—I wonder, you touched on it earlier, but maybe if you could drill down a little bit more? I wonder how her work figured into your own political evolution. What did she mean to you and what did you hope to capture in your depiction of her and her life?

Ben Passmore: I had read Assata’s book. Well, now I’ve read it several times. I read it a couple times before I knew that I was going to work on this book, and then I read it again a lot closer, obviously, when researching for the book.

What does her work mean to me? I think Assata…In a lot of ways, I just have an enormous amount of respect for the book that she wrote and also for the life that she lived. I think for a long time, I couldn’t quite understand her emphasis—particularly, actually, when she went to Cuba—with talking about ancestral relationships and spiritualism. I was not at all appreciative of anything, like, “woo.” I was not burning sage for a long time. I think more recently, I think as I’ve understood the significance of being connected to your ancestors and your people and your culture when being engaged in anti-colonial struggle, I feel like her book has opened up quite a bit more to me.

That being said, I think it’s also tough. Assata… I think she got turned into this Messiah in this way that I think she very much was not interested in. I think the fact that she lived a very quiet life for decades in Cuba…it could be for a lot of different reasons. I didn’t know her personally, although I know some people who knew her. But I think in a way… You know, I read her book again. I read her other works. I took in the spectacle around her. The way that I approached it in the book was… she is speaking for herself for maybe only two pages in the book. What we see of her in her chapter, more or less, is people talking about their version of Assata. I think that was trying to speak to how we get so much of the spectacle around her—more than anyone else I wrote about—more than we get her exactly.

That feels like such a tragedy, because her work and her writing is so candid. Any time that I’ve heard anyone talk about her, they talk about how genuine she was, how personable. She was not trying to be a figurehead at all. I think I really struggled with trying to not feed into that. Probably one of the critiques I have of the way that people talk about her sort of motivated that chapter. I found myself just very angry about her words being mischaracterized for different people’s reformist agendas. People always talking about “Assata taught me.” Then saying something that has absolutely nothing to do with her politics.

TFSR: Sure.

Ben Passmore: I always joke with a friend of mine—my friend Luke who is my research assistant on the book—but we always joke about how everyone is always talking about “Assata taught me.” But actually, no one has really read her book, which I think is tragic.

TFSR: Ben, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to me. Is there any place that you want to direct listeners? Anything that you want to promote or plug?

Ben Passmore: Thanks so much for having me. This has been great. I’m on Instagram @daygloayhole. I do a lot of regular work on there. I’m on Blusky as Ben Passmore. I have a Patreon, which is patreon.com/daygloayhole. DAYGLOAYHOLE is an old series I did. I just haven’t bothered to change the name. I do monthly reader-voted comics on the Patreon and on Instagram. So if you want to keep track of new stuff I’m doing, you can go on there. Also I’m doing a couple performances in different cities. I’ll be at a couple shows so you can you can see where I’m going on those places.

TFSR: Awesome. Thank you so much.

Ben Passmore: Thank you.